…Norway, Ireland beats China’s aid to Malawi

… UK aid shrinks

While Malawi’s diplomacy has been busy perfecting its Eastern handshake, its budget still speaks fluent Western. The Investigator analysis of the country’s aid, trade, and investment reveals that as China has been touted as the best new friend, it is old traditional western nations led by the European Union, the United States, and multilateral institutions that pay day to day, development bills.

Lilongwe seems to have been captured by easy loans but has failed to unleash development aid from its look east policy as trade imbalances has grown over the years with every partner. Again, China gets US$250 million from Malawi and only spends around US$32 annually in Malawi, according to available figures.

EU is the biggest spender in Malawi, US and the UN follows

The European Union has emerged as Malawi’s most consistent and significant partner, investing approximately €500 million per year through a massive €2 billion joint strategy spanning 2024 to 2027.

This funding, a mix of €1.4 billion in grants and €600 million in loans, is deeply embedded in the national fabric. In a landmark move in October 2024, the EU resumed direct budget support after a 12-year hiatus, injecting €55 million specifically for secondary education and public financial management.

Beyond the central government, the EU has committed €240 million to green economic transformation and over €139 million to the rehabilitation of the M1 road, the country’s primary trade artery. Even in crises, the tap remains open, with recent flood relief grants in early 2026 and €39 million dedicated to nutrition and social cash transfers for the ultra-poor.

The United States, historically Malawi’s largest bilateral donor, continues to be a financial heavyweight despite recent shifts in Washington. Though experts project a 59% decline in assistance following a suspension of programs in early 2025, the U.S. previously provided $431 million in 2023 alone.

American money is the lifeblood of Malawi’s health sector, typically providing $262 million annually for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and nutrition. A new US$700 million three programme has been signed supporting the health sector. The suspended million Millennium Challenge Corporation compact used to be a big lifeline. The scale of this support is such that U.S. aid previously accounted for 13% of the national budget; the recent cuts are expected to lead to a 1% decline in Malawi’s total GDP by the end of 2025.

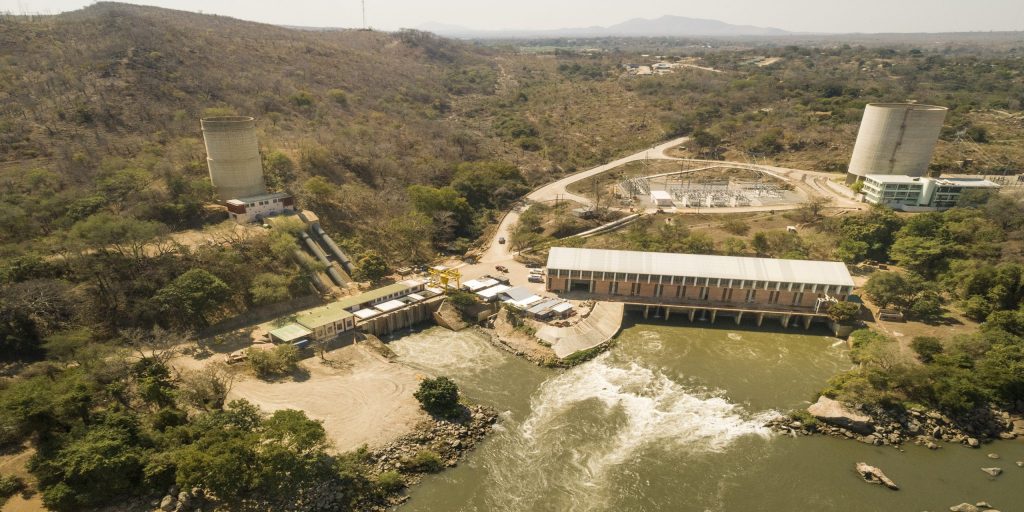

This Western-led backbone is reinforced by the World Bank and the United Nations. The World Bank is currently executing a $1.3 billion disbursement plan between 2023 and 2025, including a massive $350 million grant approved in May 2025 for the Mpatamanga Hydropower Storage Project.

The UN, meanwhile, manages a five-year cooperation framework worth $1.7 billion, though it struggled with a 50% funding gap as of late 2025. Agencies like the World Food Programme and UNICEF remain critical, spending tens of millions annually on social services and emergency food aid.

China’s low human development beaten by Norway and Ireland

In contrast, China’s current economic footprint appears surprisingly light when measured by annual spending. In 2024, China’s recorded economic activity in Malawi was just $32.87 million, consisting of $18.52 million in direct investment and $14.35 million in imports.

China maintains a massive trade surplus, exporting roughly $250 million worth of goods to Malawi, while its actual development aid is often overshadowed by smaller European nations.

In a twist of geopolitical irony, countries with populations smaller than some Chinese neighbourhoods are doing the heavy lifting; Norway and Ireland demonstrate a more consistent commitment to Malawi’s actual survival than Beijing’s grand visions.

Norway provides between $19 million and $26 million annually for health and agriculture, while Ireland’s mission strategy involves over €100 million between 2021 and 2026, averaging €17 million per year for food systems and governance. It appears that while Beijing provides the “vision,” the Vikings and the Irish are providing the vitamins.

China’s strategy rests instead on “headline-grabbing” futuristic contracts that read like science fiction compared to the humble reality of Malawian infrastructure. In 2025, Malawi signed $12 billion in transactions with Chinese investors, including a $7 billion titanium mining deal in Salima and a $5 billion Special Economic Zone in Chipoka.

However, these projects have seen little movement on the ground, sitting largely as paper commitments while China pivots toward “small and beautiful” projects like solar units and technical teams.

Beijing did, however, provide essential fiscal breathing room in late 2025 by canceling $20 million in debt and restructuring remaining obligations through 2048, effectively telling Malawians that they don’t have to pay back the loan today, but the mortgage still belongs to the East.

More investments from India, UK declines

Other international partners are also shifting their roles. India has become a major commercial player, with bilateral trade reaching $170.64 million in the 2024-25 fiscal year. India now supplies 53% of Malawi’s pharmaceuticals and has provided over $395 million in concessional loans for infrastructure since 2008.

Conversely, the influence of the United Kingdom, Malawi’s former coloniser, appears to be waning. UK aid dropped to a low of £16.3 million in 2023/24, and while it rose to £51 million for 2024/25, London’s plan to reduce global aid to 0.3% of GNI by 2027 suggests a retreat into “spreadsheet diplomacy” where the numbers keep shrinking.

Whitehall claims it will focus on Trade instead.

Germany and Japan are Malawi’s best friends

Germany and Japan remain “quiet” but vital friends. Germany’s active portfolio in Malawi stands at €342 million, with a focus on social protection and agricultural transformation.

Japan’s cumulative support has surpassed $1.1 billion, recently funding the MK 27 billion Old Town Bridge in Lilongwe and providing millions for fertilizer and sesame export capacity.

Regional support also comes from the African Development Bank, which manages an active portfolio of $222.7 million across 18 projects, ranging from hydropower rehabilitation to disaster risk financing.

Beneath the layer of state-to-state diplomacy, the Malawian economy is propped up by non-governmental organizations and its own citizens abroad. NGOs reported a staggering MK734 billion in revenue for the 2023/24 financial year, a figure that could reach MK1 trillion if all organisations complied with reporting requirements.

Malawians in the diaspora sent home $264.3 million in 2024, providing a vital cushion for rural households.

Ultimately, the data tells a clear story: the actual cheques that keep the country running are still predominantly signed in the West. Its time the country became serious on the international arena.

Editor’s View: Malawi Must Stop Collecting Friends and Start Signing Partners

Malawi’s diplomacy needs less small talk and more spreadsheets.

We import nearly US$250 million worth of goods from China. We export about US$14.5 million back. That’s not trade, that’s a generous donation program with shipping fees. Add loans instead of substantial aid, plus only around US$18 million in visible economic activity, and you start to wonder whether we joined a partnership or a clearance sale.

Yes, China is a global giant. Aligning with a superpower looked like a smart geopolitical move. But even when you sit at the big table, you’re still supposed to eat. So far, Malawi seems to be paying for the banquet and washing the dishes.

At the same time, we’ve signed away multibillion-dollar mining concessions, rutile at Kasiya, niobium at Kanyika, and more in the pipeline. These are not minor side hustles; these are once-in-a-generation assets capable of transforming the economy. Yet the promised benefits, foreign exchange, industrial growth, broad prosperity, remain stubbornly theoretical.

Diplomacy is often dressed up in polite words like strategic partner and mutual cooperation. But real friendship between nations is easier to measure: Who invests? Who builds industries? Who creates value inside Malawi instead of simply extracting it?

The truest love language in international relations is not speeches, it’s capital, factories, technology transfer, and fair ownership structures.

Meanwhile, some quieter partners, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, Japan, often show a different model: investment in sectors, systems, and skills that actually produce things. Less ribbon-cutting, more capacity-building. Less rhetoric, more return.

Malawi does not need to be a convenient market for finished goods while exporting raw hope. We need partners in production, value addition, and transparent mining deals with meaningful local participation, even serious models like 50–50 shareholding, where Malawians are not just spectators to their own resources.

Right now, the arrangement sometimes looks like this: we provide the minerals, the market, and the goodwill; others provide the invoices.

This is not about hostility. It’s about maturity. Nations, like people, eventually realise that popularity is not the same as prosperity.

Malawi’s foreign policy should focus less on who looks powerful in photographs and more on who shows up in the national accounts. Because in the end, development is not declared, it is deposited.

Time to upgrade our diplomacy from friendship status to profit and progress.

More Stories

Bank cartels fleece Malawi forex

Police, ACB jump fence in Failed Raid on Ex-Minister Kawale;

Passports delays, kabaza incidents and corruption irks APM, says Mukhito